Fantasy Islands and Bubble Trouble

by Kate Haug

My work is an exercise in nostalgia, looking back on television shows I watched as a kid growing up in Northern California’s Central Valley. I look at pop culture of that era as a form of modern mythology and I use watercolor in its loosest form in an effort to amplify that sense of odd sentimentality and test the boundaries of just how much information is needed to make a recognition. As time passes and these images become dated, their complexity and cultural significance evolves. My goal is to explore our psychological relationship with these narratives and the ways in which they both reflect and negate reality.

— Kelly Inouye 2017

“I tried to warn you about the consequences of your fantasy before you started,” Mr. Roarke says, ominously, against the paradisal backdrop of Fantasy Island’s tropical foliage, blue skies and white sands. These words, spoken by Fantasy Island’s host, contain prescient wisdom and Freudian-laced warnings. In Kelly Inouye’s timely exhibition Fantasy Island, they also provide a pop-culture parable to examine our own times: how fantasy writ large dominates our political lives and how nostalgia influences our perceptions of reality. Airing weekly on ABC from 1978 to 1984 and continuing in syndication for many years after, Fantasy Island, the television show, served as a cautionary tale on excess, ego and desire - themes ripe for Reagan-era yuppies and more potently compelling today as fantasy islands proliferate our society from narcissistically circular social media bubbles to “fake news” to the survivalist island compounds of the economically super-elite in Hawaii, New Zealand and other remote locations across the globe.

It is meaningful now to catch up with Fantasy Island as trickle-down Reaganomics and American conservatism has been realized in unexpected ways, with immense social upheaval and an economic reshuffling that dealt the middle class, the very demographic who might have been watching Fantasy Island in 1978, to the bottom of the deck. Inouye’s work evokes a lost world of suburban homes and TV watchers, of middle-class stability and the Carter presidency, of an America absorbing and processing the cultural shifts of the early 1970s. Walking into the exhibition, a white peacock rattan chair, the type used by Roarke (Ricardo Montalbon), sits in front of an immersive watercolor installation of broad jungle leaves, yellow chrysanthemums, red calla lilies – a panoply of elements beckoning you into joining the fantasy of the island. The empty chair cajoles visitors to sit down, to imagine themselves fantastically, to photograph themselves on the island, to literally become part of the fantasy. On an opposite wall, a life-sized painting of Roarke and his sidekick, Tattoo (Hervé Villechaize), greets the viewers as they do on the television show with visitors to the island. It is with immense nostalgia that we look back to comfortable, shag-carpeted living rooms with their TVs on and families gathered around a common screen to watch a show like Fantasy Island. Family lives no longer exist in that way – today each person retreats to their own screen, parents often working at home on their computers after dinner, low-wage workers often having more than one job, iPads providing babysitting duties for occupied parents. The middle class does not exist as it did in those suburban houses with good public schools, affordable college education, jobs with vacation time, fair pay and health care.

It is in this moment of great social anxiety about our future in which Inouye’s work with Fantasy Island appears. Donald Trump, a white man born into immense financial privilege and economic power, has been elected as President of the United States as a populist candidate, vowing to “Make America Great Again.” The “Again” of the campaign slogan underscores a profound, intensely emotional nostalgia for certain American voters of an earlier time period. For a time when America was great for them, when they could achieve the American dream of a three-bedroom home, economic security on a single income, food stability, medical care without bankruptcy - all generated on a 40-hour work week where it was the anomaly, and not status quo, to be contacted by work in the off hours. Inouye’s work concentrates on this murky area of wish-fulfillment and the perils of nostalgia.

Fantasy Island is a remarkably sentient framework to examine this cascading nexus of desire, the felt want for something just out of reach, for something that in its first incarnation appears as a rational demand. But as Roarke warns, “I tried to warn you about the consequences of your fantasy before you started.”A series of parlor-sized, 22 x 30 inch watercolors resonates with Roarke’s words. The paintings feature scenes from specific Fantasy Island episodes. Inouye contextualizes theses specific images with quotes from the show. In Season 1, Episode 10: Salem a couple yearning for a more simple time are sent back to Salem, Massachusetts where they are subject to the laws of colonial America which include humiliating forms of public punishment like pillorying. Inouye’s quote reads, “Did you find the simple morality and perfect life you longed for?” The line cuts deeply into today’s headlines as President Trump’s attempt to “Make America Great Again” with simplistic solutions like building a wall at the US-Mexico border or blunt instruments like the Muslim travel ban. These actions test the framework of our democracy and constitutional rights, which demand careful and complex thinking to maintain their functionality and longevity. Our desire, our fantasy of disengaging from the intricacies and rigors of our democracy make us prey to a more simplistic form of governance, appealing in its plainness, harrowing in its execution.

Season 1, Episode 10: Salem, Watercolor on Paper, 30 x 22 inches, 2017

Another strong theme of fantasy within Fantasy Island and on-going American history revolves around colonialism and the commercialization and commodification of the Pacific Islands. The “return to nature”, as a conduit for people to find one’s “truest” most “primal” self is standard fare within popular culture. From Paul Gauguin’s 19th century Tahitian paintings to the Tiki Bars of the 1950s to the current popularity of Peruvian ayahuasca ceremonies, this exploration of an alternative self away from the moral confines of society as the harbinger of true wisdom and colonialist knowledge runs deep within mainstream American culture.

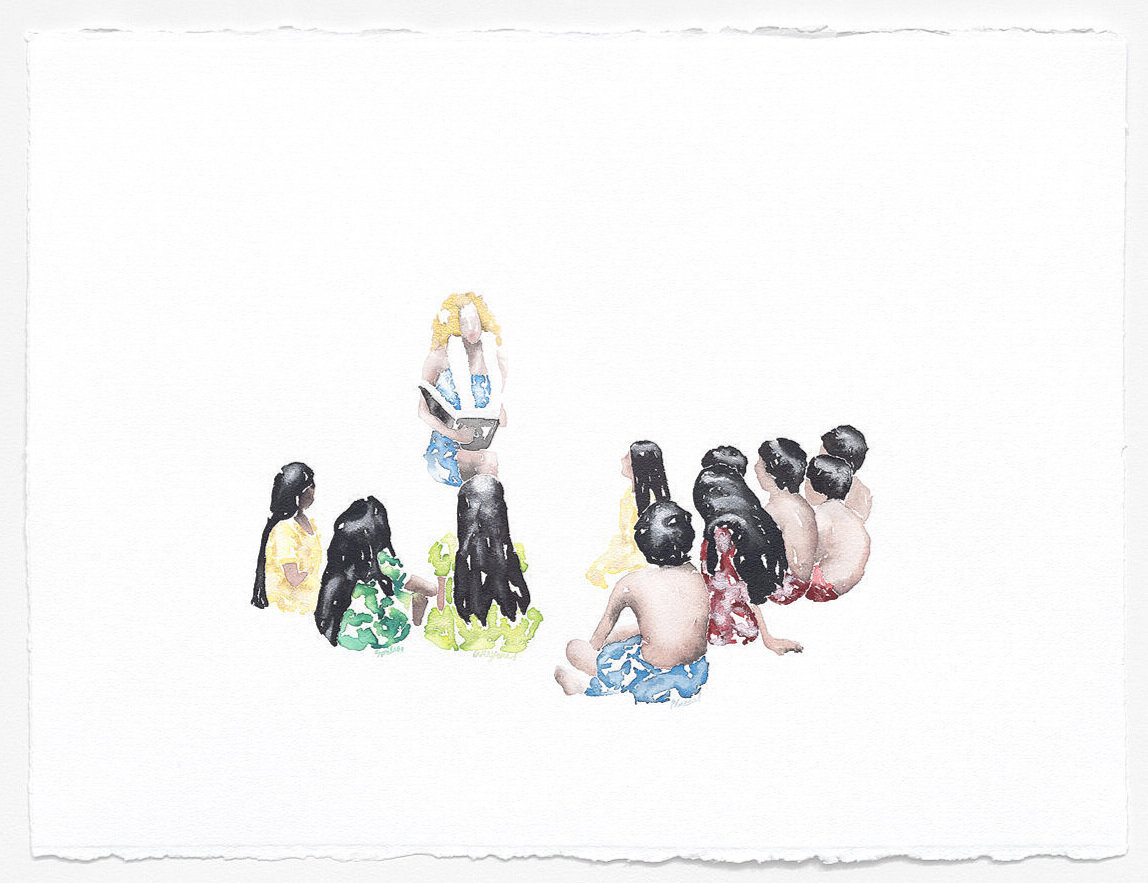

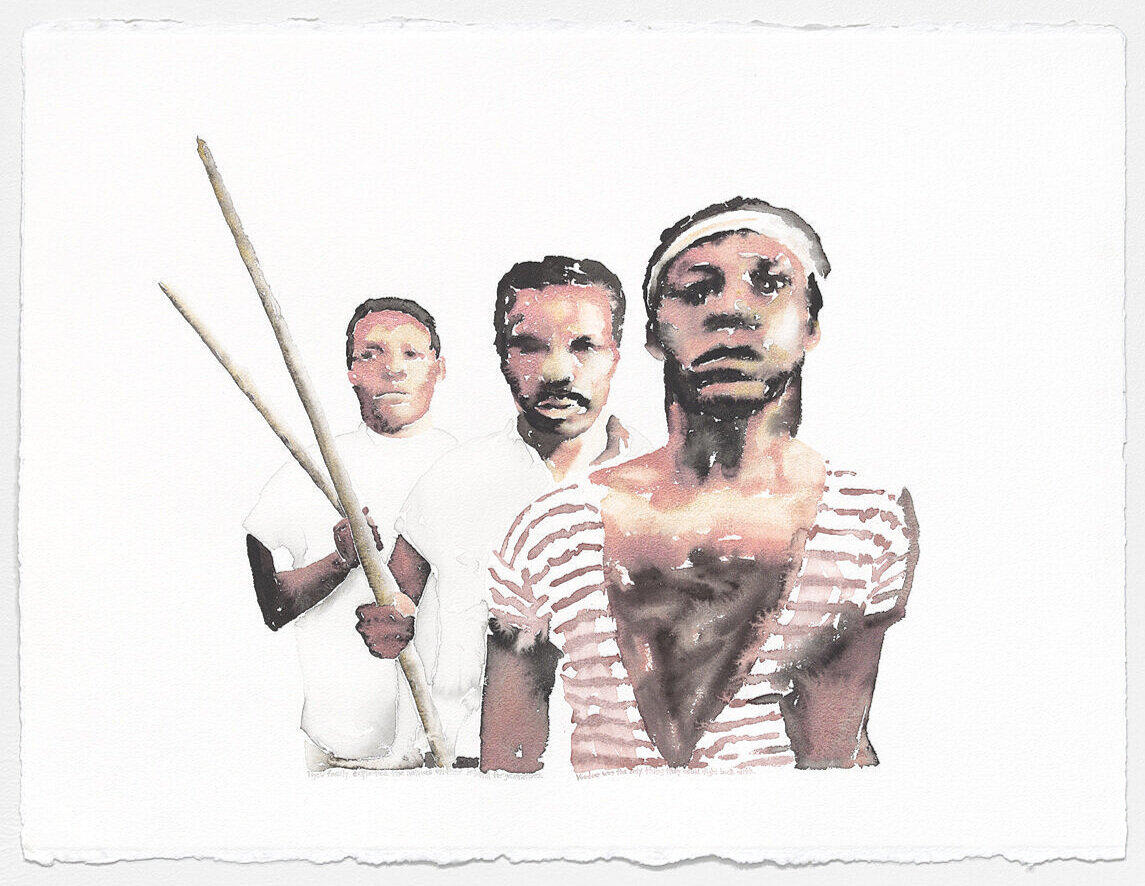

Inouye examines the show’s re-affirmation of troubling colonial tropes within two paintings – Smiles, everyone! Places! and Season 1 Episode 6: Voodoo. In Smiles, everyone! Places! a young white woman, sparkling gold hair, Hawaiian lei and strapless tropical print dress, sits elevated with a circle of dark-haired children around her. It’s the 80s version of the white missionary cheerfully giving the gospel to the “natives”, who in this setting are actually paid child-actors from the Los Angeles area and its suburbs. Three dark men, two with sticks confront the viewer in Season 1 Episode 6: Voodoo. The quote Inouye uses is profound in its reference to both American slavery and the colonial plantation practices found not only in Hawaii and the Caribbean but many places across the globe: “Their family exploited the natives on their island for five generations. Voodoo was the only thing they could fight back with.” Voodoo as a perceived means of resistance not only underscores the colonized lack of political agency but the colonizers inability to perceive or comprehend their fellow human beings. Through the lens of Hollywood, these three actors become a hyper-romanticized oversimplified, exotic “other”, and the story ends there. Inouye forces us to pause and re-contextualize this image in 21st century terms.

In Season 1, Episode 2: Return to Fantasy Island Inouye’s painting of a shadowy ghost-like male character forcing a woman to the ground stirs up feelings of rape and dominance by an undefined patriarchal culture. It is an uneasy image, one that has been seen in popular culture, on television, at the movies for decades. The incorporated quote reads, “They’re fighting for equality, Tattoo. I wonder if they find it, will they even recognize it.” The image is appropriated from an episode in which a male assistant, in love with his boss, a female executive, wants Roarke to make him her savior. In his fantasy, he and his boss come to the island, which transforms into a primitive, pseudo-Neanderthal epoch. The woman is subsequently captured and kidnapped by one such Neanderthal man (Roarke disguised) so that her assistant can save her, embodying the supposedly more robust physicality of men during a more primal time when, men were men and women were subject to them. Currently, we have a president who is a confirmed “groper of women,” echoing this type of nostalgia in which misogyny becomes a quasi-romantic trope re-instilling a false natural order between the sexes. Here again, the desire to eradicate complexity in favor of less-demanding modes of understanding undermines an aspiration for equality.Fighting for, finding and recognizing equality were some of the main directives of late 20th century liberal democracies. Yet, in our current political climate with its wish to ignore reality, to live in fantasy, we potentially throw-off our legislative quest of finding, recognizing and legislating equality in favor of mythical economic solutions where men are men and women are subject to them.

Kelly Inouye, Season 1, Episode 6: Voodoo, Watercolor on Paper, 30 x 22 inches, 2017

Where do television and watercolor merge into this current history of fantasy, of nostalgia? Historically, television was a populist medium, born in the dawn of the middle class, populating homes with its blue-lit screens in earnest in the post-war era, a time period forever associated with the birth of the suburban, middle-income wage earner, the Leave it to Beaver times, when steady bourgeois, church morals were the political and dominant cultural mainstream.

1970s suburban living room, photographer unknown

Watercolor is also a populist medium frequently associated with hobbyists, weekend painters and gentle souls, concerned less with status objects and more with scenery, birds, botany, public scenes, cafes and landscape. Unlike oil painting, watercolor has been linked to women; crafty females who have a creative streak. It’s probably not a coincidence that the surface of the water color, with its undefined edges, its vague references to object-hood and verisimilitude, does not fix objects and people with the same authority of line, of depth which oil painting does and is therefore seen as more feminine and more, even, perhaps at ease with the temporality of life, moment by moment. Inouye’s use of watercolor in this context brings us to the blurred surface of this recent history, which still lurks in our subconscious. Inouye’s use of television shows is a poignant reminder of what was, what is deep in the DNA of many so-called “latch-key” kids who lay on the floors in their family rooms after school and watched syndicated re-runs and then later watched the evening news with their parents, watched Jimmy Carter during the Iran hostage crisis and Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign. Watercolor is the perfect medium for this introspection and this loss because of its history as a populist medium. It is the perfect vehicle to represent the desire for a middle-class security, an emotional nostalgia rather than an elitist culture, which is often the purview of oil painting. Watercolor, as a medium, belongs to the people, whereas oil painting was often the master’s medium, representing the rarified world of capital in terms art collectors, art collecting and subject matter. One only has to imagine a John Singer Sargent portrait, luminously wealthy, luminously fleshy women in satin dresses and slyly glittering necklines. Sargent’s paintings stand in museums as objects of desire containing objects of desire, the fantasy of order, of class sanctity.

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Madame X

Watercolor is the perfect medium for this introspection and this loss because of its history as a populist medium. It is the perfect vehicle to represent the desire for a middle-class security, an emotional nostalgia rather than an elitist culture, which is often the purview of oil painting. Watercolor, as a medium, belongs to the people, whereas oil painting was often the master’s medium, representing the rarified world of capital in terms art collectors, art collecting and subject matter. One only has to imagine a John Singer Sargent portrait, luminously wealthy, luminously fleshy women in satin dresses and slyly glittering necklines. Sargent’s paintings stand in museums as objects of desire containing objects of desire, the fantasy of order, of class sanctity.Nostalgia is defined as “a sentimental longing or wistful affection for the past, typically for a period or place with happy personal associations.” The quixotic comforts which nostalgic moments evoke are clouds of remembrance. Inouye’s watercolors work in this dreamlike consciousness, standing in that place between memory and reverie; the scene is recognizable but not realism, faces are known but not explicitly described. Inouye’s watercolor is exceptional in its scale, forcing it outside of the domestic realm, pushing the boundaries of the medium, posing questions about femininity and masculinity within painting. Lush flowers evoke a tropical landscape and also physical sensuality. Up close, they exist as abstract painting, the ebb and flow, the density and thinness of the paint revealing the weighty flow of water and pigment on the paper. The surface of the images ask the viewer to think about the nature of representation, of how the surface is functioning as both representation and also detournement of the image, of the hijacking of expectations, similar to the way nostalgia functions on Fantasy Island, as a way of rethinking our desires. Inouye further complicates her surfaces by her use of iridescent paint, which brings a tem-poral element to the image as it changes under different light, subtly reflecting the angle of the sun, the light of night. Inouye’s iridescent is not John Singer Sargent’s oil paint but the shimmer of Studio 54, an-other moment, another class, referencing the aspirational surfaces of the late 70s. One can imagine Jerry Hall reeling into Studio 54 golden locks, gold lame shimmering like the lip gloss on Grace Jones, the reflections of coke mirrors, foreshadowing the Miami Vice (1984-1989) homes of the Reagan nouveau riche. The surface is sexy like disco, the glittering skin of decadence, not affixed in oil but in the moving flesh of the excesses of the middle class, Saturday Night Fever, cheap thrills, thin fabrics, shiny people. The peacock chair Inouye includes produces a temporal circularity within the exhibition. As people will undoubtedly Instagram themselves in the chair, there is a fluid connection between screens of the past and screens of the present. People will pose themselves in the chair, inserting themselves into Inouye’s jungle scene and into their own reflections of Fantasy Island. Their personal images uploaded and seamlessly shared, screen to screen, eye to eye, palm to palm.

Kelly Inouye, This place is too much, installation, dimensions variable, 2017

We have moved from a place when television was a backdrop to our lives, the surface, which chronicled aspects of our culture, to one where everything becomes backdrop to our own brand, our own island, our dispersed culture. We are boats floating past a succession of islands, our screens our eyes. In this way, Inouye’s installation is not merely a nostalgic look at a TV show but a conduit to our own, contemporary psyches. It’s a timely coincidence when, post-election, one finds pop stars like Katy Perry singing, “Are we crazy? Living our lives through a lens ... So comfortable we’re living in a bubble, bubble/So comfortable we cannot see the trouble, trouble.” Unlike Sargent’s oil paintings, upholding the security of class order, Inouye’s exhibition points to the fragility of class. Her watercolors, in their grand-scale and dreamlike scenarios, are surfaces, which provoke the temporality rather than the fixed nature of our experience, the tenuousness of our past to predict our future and the pain of what is lost in our fantasy pursuits.

Kelly Inouye, Roarke and Tattoo, Watercolor on Paper, 47 x 80 inches, 2017